The Energy Industry is in danger of losing its licence to operate. Rightly or wrongly, it is being blamed for increases in the wholesale costs of gas and power which are largely beyond its control. Exposure to gas prices is driven by failures to rollout energy efficiency, late delivery of new nuclear and renewables and overexposure to the continent. These factors drive and exacerbate inflation which will likely be responsible for a recession as businesses and households reduce activity and spending in response to rising energy prices.

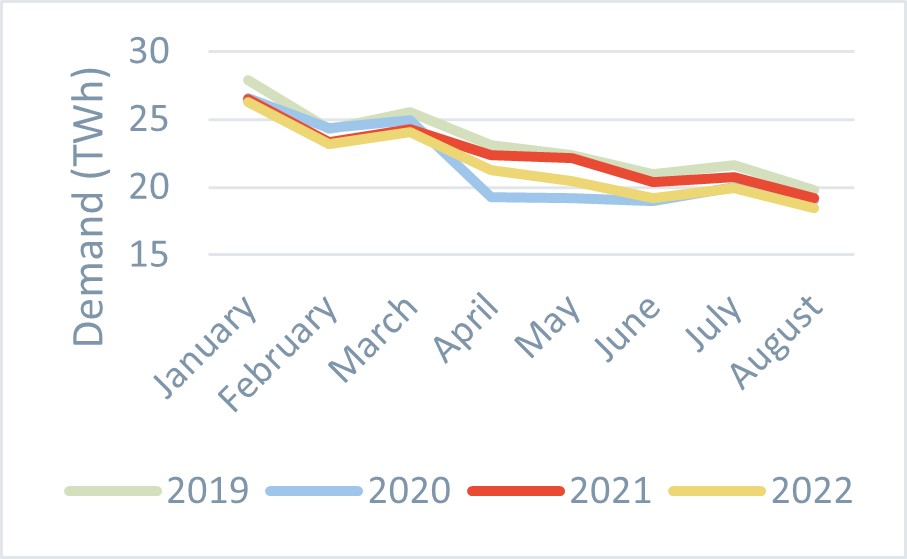

Year to date power demand in 2022 is down 6.9% compared to 2019 and 3.4% compared to 2021, 2022 is only 0.21% higher than 2020 during the height of the pandemic. Price response and demand destruction must be playing a role with (as of 19/08/2022) day-ahead power prices being up 274% year-on-year and season-ahead power prices being up 688% over the same period.

Source: Cornwall Insight, NGESO Data Portal

Absent any support for business users and households this winter, demand is likely to be lower than originally anticipated in the early outlook for winter 2022, and we are at lower risk of blackouts and scarcity but at the cost of shuttered businesses and rising inflation.

Assuming there is a short-term fix applied to the wholesale or retail markets to see us through this winter, eyes turn to the medium to long-term and what kind of market might suit us better in a brave new world. Does the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) have the potential solution which would help us avoid similar situations in the future and win back confidence in the energy market?

REMA Solutions

REMA is intended to develop a market solution for achieving a net zero power system in 2035, the design should be able to cope with:

- Rapidly deploying capacity required to replace aging assets and new assets required to meet targets, such as the new renewables capacity needed to meet net zero.

- Large variations in power output and demand over relatively short periods of time, such as swings in wind and solar outputs within the day.

- Investing in the right capacity at the right place, such as siting renewables in places where they get the most out of the natural resources but don’t drive up the cost of networks.

- Volatile power markets driven by uncertainty in whether patterns and demands swinging between the marginal cost of renewables (close to zero) and the marginal cost of flexible generation (potentially very high).

In the scope of the assessment are the wholesale market structure (such as the Balancing and Settlement Code, bilateral contracting and power market exchanges), renewable support schemes (such as the Renewables Obligation (RO) and Contract for Difference (CfD)), security of supply arrangements (such as the Capacity Market, or Ancillary Services).

The two leading options which have garnered the most airtime are the move to a central dispatch Locational Marginal Pricing System and the idea of market splitting, where there would be separate market arrangements for low marginal cost zero carbon power and for high marginal cost flexible power.

Locational Marginal Pricing

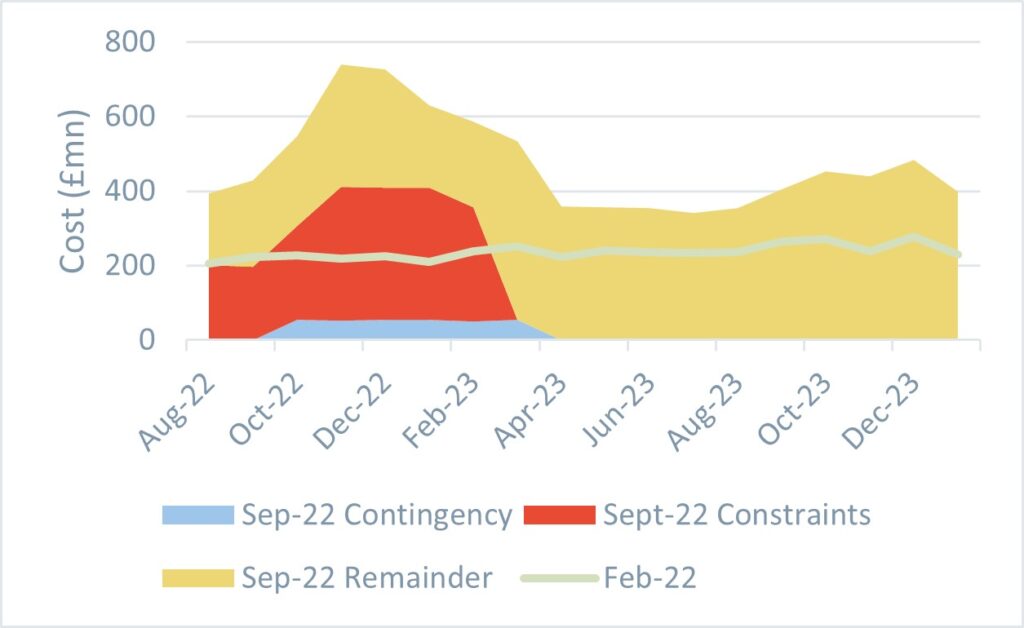

The cost of operating the electricity system is as exposed to the price of gas as the retail and wholesale markets and has risen accordingly. The latest forecast for BSUoS costs has increased to a total cost of £3.7bn over the October 2022-March 2023 period, this is an increase of 174% compared to the forecast prepared by NGESO in February 2022 before the Russian invasion.

Source: Cornwall Insight, NGESO Data Portal

Of this cost, the majority is constraint spending, which, in the latest 6-month forecast, accounts for 43% of the total balancing cost over the winter period. In comparison the new £320mn for the winter contingency contracts makes up 9%.

Imperfect dispatch of the electricity market is therefore expected to cost consumers at least £1.6bn this winter, and many have argued an established market design used in other jurisdictions, like Texas or New Zealand, could reduce this cost by exposing market participants to a locational signal.

Locational Marginal Pricing, a design proposed by the ESO in its review of optimal market designs, would take information on capabilities and prices from market participants. The ESO would then dispatch the market at lowest cost within the constraints of the system, which would result in different prices in different regions. In effect, rather than socialise the cost of constraints across the system, the LMP design would reflect this onto generators. Those causing or exacerbating the constraint would see lower prices or dispatch volumes, and those which could relieve or replace the constrained generation would see higher prices or dispatch volumes.

This would expose generators to the effects of their decisions of where to locate, and would incentivise different behaviour, such as encouraging demand, investing in storage or different siting locations. The counterargument is that generators would be exposed to hard to forecast costs, increasing the difficulty of investment and jeopardising investment to meet targets.

Source: Cornwall Insight

Concerns have been raised about the current bilateral energy market design, where the marginal generator price is used as a benchmark for power prices, which potentially over rewards low marginal cost plant, in the case where there are constraints low-marginal cost plant would see lower prices more reflective of their costs. However, in area where there are low constraints the low-marginal cost generators would still be cleared up to the price of the marginal (possibly gas-fired) generator.

When we have modelled a LMP system in GB, based on the GB transmission system, while prices are quite diverse in Scotland, over much of England and Wales the prices are very similar. As most wind capacity is located in the North, there could be a significant saving for GB consumers, while solar generators and offshore wind farms located on the East Coast of England will be less affected.

It is unclear an LMP market would improve security of supply or reduce reliance on imports of gas and power. Interconnectors might be more effectively located, but building capacity in GB itself could become more complicated as the increased volatility of wholesale power prices reduces the visibility and bankability of generator revenues.

The LMP market design is unlikely to be able to deliver change within the next two-to-three years, the IT systems change required would require a significant lead time, which NGESO estimates would take around five years, not to mention the need to design new LMP compliant capacity and renewables support schemes.

Market Splitting

Another front runner for market design in REMA discussions, is the split market, where a separate price is determined for low-carbon variable power and firm power. Prices for the variable low carbon market would be determined via long-term agreements and be close to the long-run marginal cost of the renewables participating and in the firm power market the prices would be set by the marginal cost of whichever generator is providing firm power.

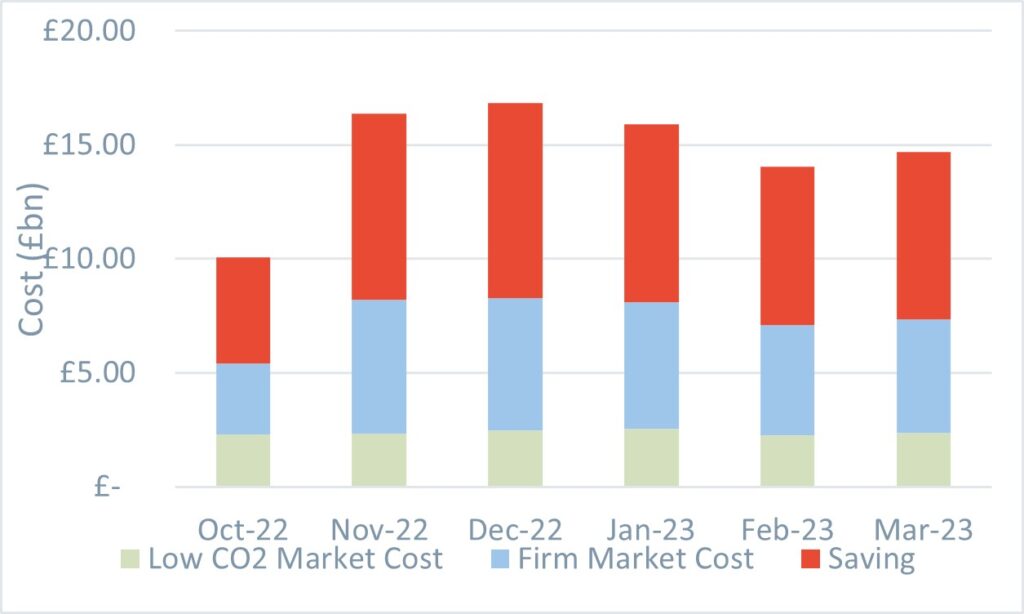

Source: Cornwall Insight, NGESO Data Portal

Again, this would not be a quick fix, there is no market template to learn from in another market, and the central purchasing arrangements would require new market agencies combining the roles of the Low Carbon Contracts Company, National Grid EMR and suppliers. A centralised low-carbon contracts purchasing agency like this could have additional benefits, such as transparency on each contract procured and allowing these Power Purchase Arrangements to be traded onwards. This would allow consumers to engage directly in the market and could provide a route to move away from central allocation to competition.

The attractiveness of this concept for addressing concerns in the short-term is illustrated by the effect it could theoretically have this winter. For example, using average monthly load factors and demand from last winter, capacity under the RO, Small Scale Feed in Tariff (SSFiT) and firm fossil fuel fired generators would earn £87.9bn between October 2022 and March 2023, at current monthly prices.

If we were to declare an emergency market split, where nuclear and renewables under the RO and SSFiT were to transfer into a separately priced market or administrative CfD, where the price is set at the baseload reference price for winter 2021-22 (£102.5/MWh) and the cost of a ROC (£59.7/MWh), the overall revenue would reduce by £44.4bn. This would be an enormous transfer of wealth and come with serious implications for investment and operation of low-carbon resources in the UK. Given the average price for winter baseload power is £656/MWh this is unlikely to be attractive for generators, who could be encouraged onto the scheme by being offered an option to extend after 3-4 years if they repower the site.

Emerging on the other side

As we emerge from what is likely to be a difficult winter in spring 2023, we will be looking to learn lessons about what led to this situation and how to improve the situation which is likely to persist for a number of years. We cannot yet diagnose with certainty the failings and issues of the winter, but it is likely the high priority issues will be:

- Diversity of fuel sources, relying too much on any one kind of fuel or source of that fuel. For example, gas can expose the market to security of supply issues.

- Resilience, there is very little slack in the system on both a demand and supply side, and there has been too much focus on efficiency and not enough on investment.

- Profitability, some business models are unprofitable leading to costly failures, while rising costs have led to accusations of profiteering.

REMA could easily encompass these additions in scope and pave a way for a more resilient and secure and stable system that also addresses the need for an acceleration in investment, additional volatility and locational constraints on decision making. If properly resourced and given enough focus, the review could design a market that addresses these issues which are likely to be more prevalent in a world where energy demand is supplied by variable renewables as well geopolitically uncertain fossil fuels.

This is an excerpt taken from our Industry Essentials (GB) service. If you are interested in learning more about the Industry Essentials (GB) service, please click here.

If you would like to access all your services in our customer portal, CATALYST, please click here.